On Coding Agents and the Future of Design

In his seminal 2010 article on responsive design, Ethan Marcotte described a new way of thinking about web user interfaces that moved beyond a fixed frame. Reacting to his clients’ requests for an “iPhone version” of their websites, he suggested instead a single experience that could respond to the user’s device. Page elements could use a different set of design properties for large screens and small, transforming their form to match the capabilities of the hardware. Crucially, on simpler devices, elements could be hidden entirely if deemed non-essential.

As this technique became popular among designers and product teams, they quickly realized that it was more challenging to start with the “full” version and pare it down. Instead, by starting with the least capable device, you could boil the product offering down to its essence and present those primitives in the limited screen real estate available. This soon led to an acknowledgment of the irony of responsive design: That the least capable devices often had the most effective user experience, as they were most closely aligned with user needs.

We came to realize that responsive design wasn’t just about layouts, it was about forcing organizations to confront what actually mattered. But organizations, it turns out, cannot resist the temptation to use available UI space for promotions or expressions of their org chart, all of which almost always get in the way of what users are trying to do. That this still remains true all these years later is astounding; the difference in the UX of apps versus websites for banks, airlines, and ecommerce is stark evidence1.

Towards a More Radical Responsiveness

I believe we’re at the beginning of a new era of further crystallization, and it feels both more disruptive and more enabling than the shift to responsive design 15 years ago. Earlier last year, foundation model providers released coding agents that developers could install and use directly from their command line terminals. These agents, including Claude Code and OpenAI Codex, introduced two seemingly small advances that would turn out to be incredibly significant.

First, they could iterate. Unlike earlier chatbot interfaces, these agents would continue to work and refine their output, looping over a plan until its goals had been achieved. Second, they were given access to tools. They could now call standard Unix utilities like curl for loading web pages or grep for searching file contents. A few months later, the underlying models were updated specifically to take advantage of this kind of tool use and to stay more focused on plan-following. With those pieces in place, developers on the frontier of AI-assisted engineering began sharing new workflows that felt genuinely different and everything sped up again.

Recently, many non-developers, myself included, have found that using Claude Code with files locally can be an incredibly effective way to get work done. My social feed is filled with people sharing their use cases: setting the agent to work on an Obsidian vault, managing email and calendars, finally getting value from smart home devices.

Primitives All the Way Down

The key to all of this is the tools: small, simple command-line apps with clear, direct documentation. Despite the promise of MCP servers, Claude Code with access to iCalBuddy is a much faster and more effective way to ask for help organizing next week’s schedule. Codex is an expert with gh, the CLI app for GitHub, and can quickly summarize and organize your next sprint’s outstanding issues. Both can quickly navigate through 1Password with the op command to avoid spewing access tokens everywhere2. These apps so clearly expose the primitives of the systems behind them. An agent looping iteratively while stringing dozens of these composable tools together starts to feel like a very new way of working.

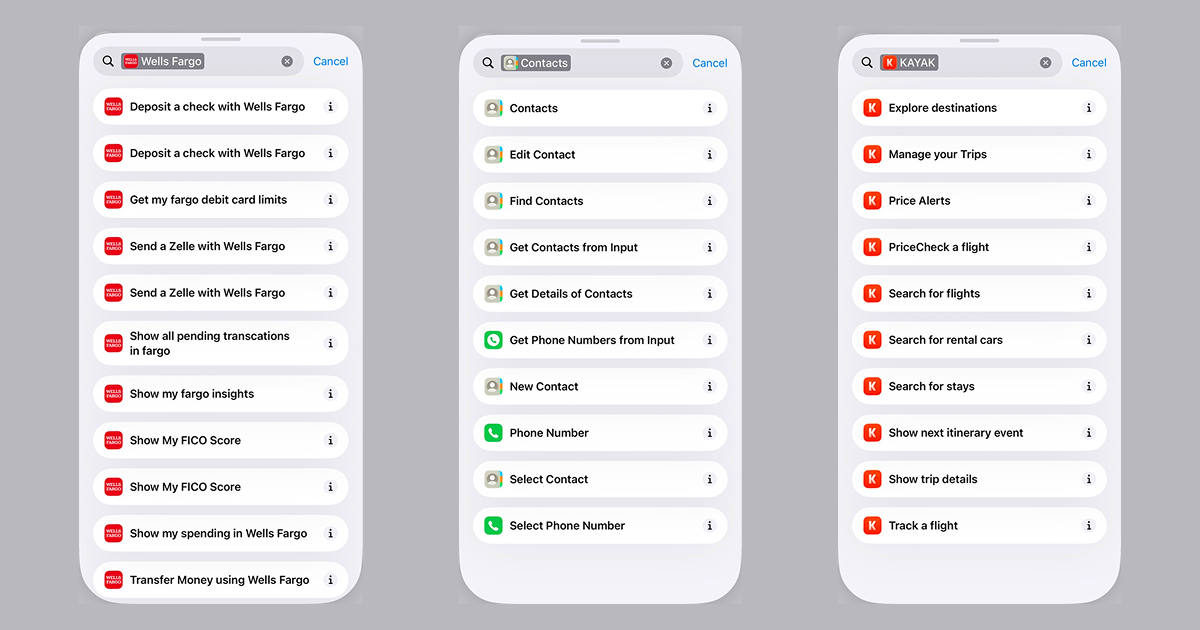

This is the next step in responsive design and the blueprints are lurking all around us. The coding agents now let you add skills — simple descriptions of how to accomplish a task written in natural language. You might explain to your agent how to get data from an internal API to help you create your quarterly update, for example. But if you really want a great look at what the future may hold, try this: on an iPhone or Mac, open the Shortcuts app and start searching through the available commands exposed by each app you have installed. There, you’ll find a remarkably clear visualization of all the atomic components of an app’s capabilities. All the nouns and verbs.

None of that works with agents quite yet3, but I think this is the clearest glimpse into what apps become in a world of advanced agentic workflows. Here in three screens are the actions we can take when communicating with friends, planning our vacations, and managing our money. This is what it looks like when apps are honest about what they can do. And a step further: all the APIs for all the enterprise SAAS and personal productivity apps, lurking behind developer documentation, waiting to be unlocked. What is a “seat” and what is a “user” when we send our agents to ask questions and make requests? This isn’t just app design, but what businesses become as we collectively lean harder into agents.

Clarity as Competitive Advantage

This may seem counterintuitive, but my career in user experience design makes me even more excited about a potential future like this. If agentic workflows strip back applications to their bare essence, then it makes sense that they’d present what they find in UI components crafted on the fly. Perfect customization, whether you’re accessing the capability on a large display or through your AirPods, in English or Cantonese, wrapped in shadcn or Chakra UI — your choice!

An agentic future elevates design into pure strategy, which is what the best designers have wanted all along. Crafting a great user experience is impossible if the way in which the business expresses its capabilities is muddied, vague or deceptive. So the best have always pushed for more authority, more access to the conversations where the real decisions are being made in their organizations. To gain that access while maintaining advocacy for humans using the products has always been my goal as a designer.

This takes a pretty big leap of faith for those practicing design. I see the same happening for engineers waking up to the fact that they’ll soon stop typing code, and not long after that, stop reading it. Many of us are imagining futures in which aspects of the labor we love are quickly slipping away. But I’ll argue it’s what we’ve been after all along: Responsive designs that mold to our customers and patients and citizens in ways that ask businesses and institutions to express to us exactly what they have to offer.

If an agent used your product tomorrow, what truths would it uncover about your organization?

-

I have known Ethan for a very long time and have much admiration of his work and the powerful and positive influence he’s had on the design community. I’m also aware of Ethan’s clear and reasonable commentary on the ethical implications and environmental impacts of LLMs. Citing his work here is done with the utmost respect. ↩

-

Let’s not discount the security implications here. They are dramatic. But we need use cases to solve for, rather than blanket bans. ↩

-

You might not find better proof of Apple’s missteps with Apple Intelligence. The raw materials are all there; they’ve already shipped the hardest part. ↩