When to talk, when to work

Very few successful products come to market exactly as expected, but Flickr really took it to a whole new level. It was built by a handful of people, emerging out of an online game. They added chat to their game, then photos to the chat, then web pages for the photos, and suddenly found themselves with terabytes of images – all before they even came out of beta.

So, there is a lot to learn there. One of the original developers, Cal Henderson, was in San Francisco last week conducting a workshop/extended-case-study on some of the more technical lessons they learned. Tom Coates of plasticbag.org posted an excellent overview, which I won’t attempt to recreate here. But I will echo his interest in Cal’s abstraction on their application, and the implications on team structure, communication, and collaboration.

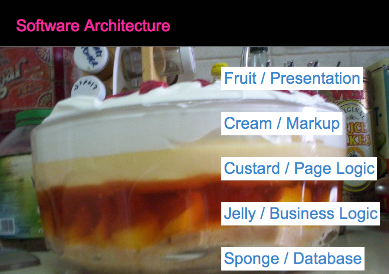

_credit: Cal Henderson

Cal was the first to admit this method of abstracting a Web application isn’t all that innovative. There are variations on this theme everywhere you look. But what I found the most interesting were his comments on how this abstraction leads to more efficient team communication. By compartmentalizing each discipline, everyone knows just what to work on, what the structure and constraint of that work is, and how to ask for what you need from the people up and down the chain.

“Hmmm…” I thought. “That hasn’t really been my experience.”

I thought back to my time with Lycos, after they acquired HotWired. We had a similar abstraction, but with a difference: size and distance. Lycos was a far cry from an eight-person startup, and was stretched between two coasts, and later three continents. The abstraction that Cal was describing was used _instead of communication on our teams. Instead, back-end developers would have specs pushed on them by “business owners” and then write code that dictated how designers could and couldn’t create pages.

The abstraction and separation of disciplines brought out the worst in everyone working projects. The hubris of talented engineers (“Why is it so hard to make our amazing web app pretty?”) versus the inflexible elitism of designers (“Those buffoons would set everything in Arial if we let them!”). Needless to say, it wasn’t the best working environment.

So, with this in mind, I asked Cal how it worked in practice. And he answered, “At flickr, there are two teams: those who do the interaction and markup and user stuff, and those who do the hard stuff.” At which point I had a flashback to my days at Lycos and started shaking my head.

But as we kept talking, and I realized the piece I’d always missed. At flickr, the development started with just a few people. When they reached a point of needing help (or, probably more accurately, being able to afford help), they brought another extremely talented person into the mix. Then they did that a couple more times, but slowly. And all of this originally happened in the same office – actually, in the same room. Close-knit collaboration between extremely talented people.

So it turns out Cal and I agree after all – the abstraction of a tiered architecture is an efficient way for people to work, communicate, and collaborate. But that seldom works without a deep respect built from working together side-by-side, at least at first. In other words, _designing things works better together, and _building things works better with structure.

And nothing worked well at Lycos…